The gruesome diet of medieval Europe: why embalmed mummy bodies were eaten in ancient times

It is striking how little respect Europeans had for the dead that they began to use their bodies for various purposes. Arab and Persian traditional medicine used natural bitumen. Even Avicenna (Ibn Sina) in the 11th century described its benefits for the treatment of abscesses, fractures, bruises, nausea, and ulcers with mumia (wax). At the same time, the works of Arab and Persian scholars were translated at the University of Salerno in Italy, where they did not know about mumiyo and nothing was explained in the works about it, because everyone in the East already knew what it was. But Europeans interpreted the word as follows: "It is a substance that can be found in the lands where bodies are buried, embalmed with aloe, with which the body fluids are mixed and turned into a mummy," wrote the Italian scientist Gerard of Cremona. In the 13th century, all of Europe was convinced of the healing properties of mummies from Egyptian tombs.

In the 15th century, Egyptian mummies were seriously considered a medicine. Tomb robbers started their business here. Particular attention was paid to poor and relatively fresh burials. Bitumen was indeed found there: it was used for embalming instead of expensive sodium lye and gum (tree resin). The resin mixed so strongly with the tissues of the deceased that it was impossible to distinguish between the bitumen and the actual body of the deceased.

In the 16th century, mummies were already in full swing. There is an assortment of mummies: mumia vulgaris (common mummy), mumia arabus (Arabian mummy), mumia sepulchorum (mummy from tombs). Mummies are becoming extremely popular in Europe.

In 1580, an Englishman wrote: "The bodies of ancient people, not rotten but whole, are dug up every day. These dead bodies are the mummies that doctors and apothecaries force us to swallow against our will."

The demand is so high that fraudsters begin to offer the corpses of criminals under the guise of mummies. In 1564, Guy de la Fontaine, a physician to the King of Navarre, was brought to a mummy trader in Cairo. He said that he was preparing the medicine himself and did not understand how Europeans could use such an abomination.

The upper classes began to treat mummies. For example, King Francis I of France does not go hunting without a bag of mummy powder. By the way, the practice of eating corpses was normal for that time, because doctors themselves prescribed such "treatment." King Christian IV of Denmark, for example, used the ground skulls of executed criminals as medicine. The only drawback of the medicine was that it did not work. The doctors themselves admitted that mummies do not help in treatment.

Read also: A 6000-year-old settlement discovered in France.

In the 17th century, the fashion for mummy treatment slowly faded away, and the French botanist Pierre Pomme even advised luring fish with mummies.

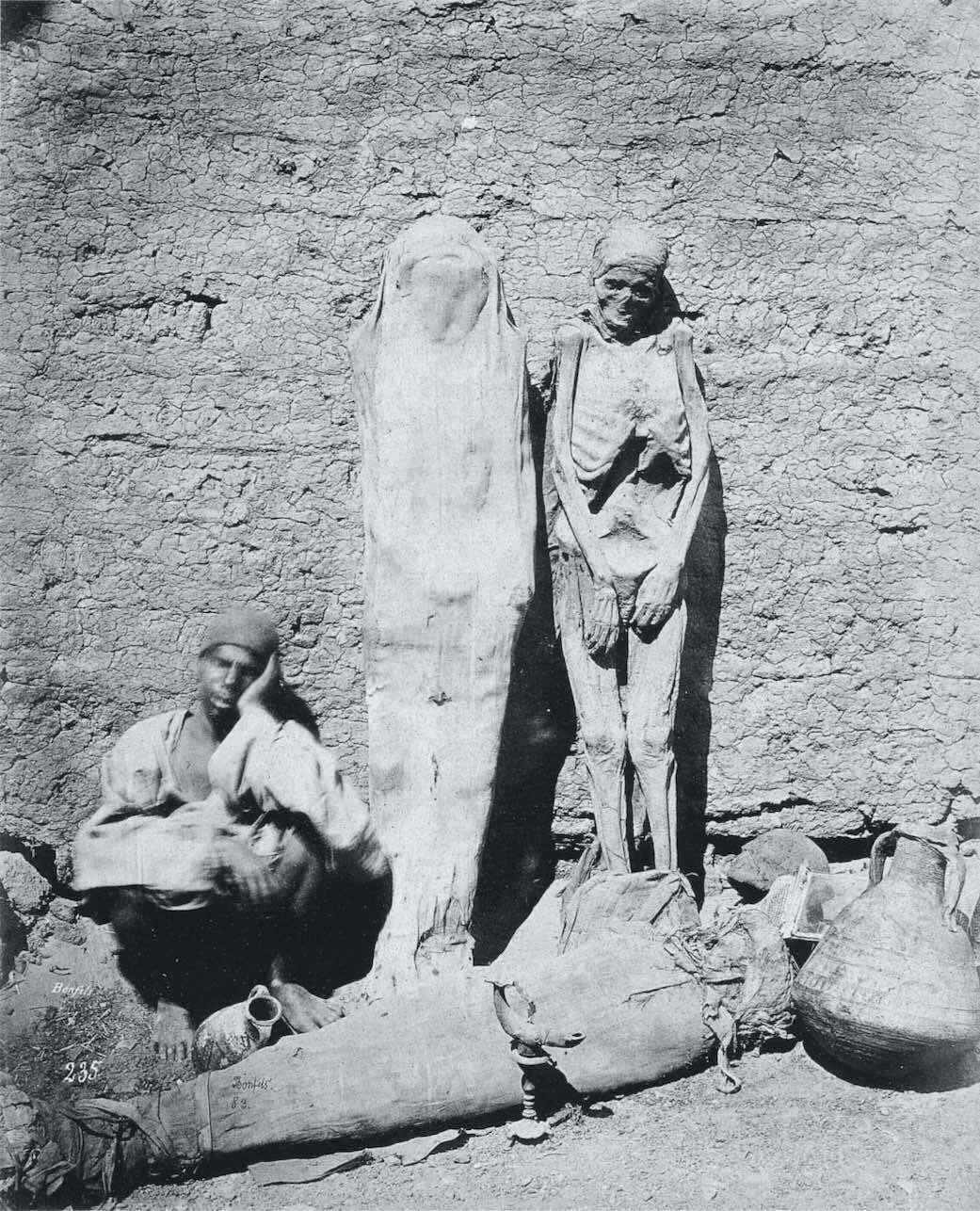

In the 18th century, mummy treatment was recognized as quackery. But in 1798, Napoleon went on a campaign in Egypt, and this created a mania for everything Egyptian: papyri, scarabs, and mummies were bought by Europeans on an industrial scale. On the streets of Cairo, it was commonplace to meet a trader selling whole mummy bodies. However, parts of mummies were more commonly sold.

In the 19th century, parts of mummies were still sold in Egyptian markets. Heads were the most popular, and mummies from rich tombs were the most expensive. Prices were low: a head could be purchased for 10-20 Egyptian piasters. All the goods were illegally exported to Europe. By the way, the writer Gustave Flaubert had a mummified foot on his desk for 30 years, which he found in Egypt.

"It would not be very respectable to show up in Europe after returning from Egypt without a crocodile in one hand and a mummy in the other," wrote the monk Ferdinand de Jerambee in 1833.

Only in the late 19th century did people realize that they should respect the ashes and graves of Egyptians. However, artists continued to use mummy powder as pigments for their paintings until in 1837, the English chemist George Field wrote in his treatise on paints and pigments: "We will not achieve anything special by smearing the remains of the wife of some Potiphar on canvas, which can be achieved with more decent and stable materials."

As a reminder, a mysterious structure was found in the desert in Oman.

If you want to get the latest news about the war and events in Ukraine, subscribe to our Telegram channel!