The story of saving Egypt's most valuable ancient monuments from flooding: the feat of Christiane Deroche

In the early 1960s, the story of an international campaign to save some of Egypt's most precious antiquities from sinking grabbed headlines around the world. But the massive press coverage of this extraordinary rescue operation overlooked the brave woman French archaeologist who made it happen. If not for Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt, more than 20 ancient temples would have been swallowed up by the flood waters of the new giant dam.

In the eyes of the Egyptian government, the loss of the treasure, while unfortunate, was necessary: The Aswan High Dam was needed to boost agriculture and provide electricity to Egypt's rapidly growing population. "What else can we do," said one young engineer who worked on the project, "but drown the past to save the future?"

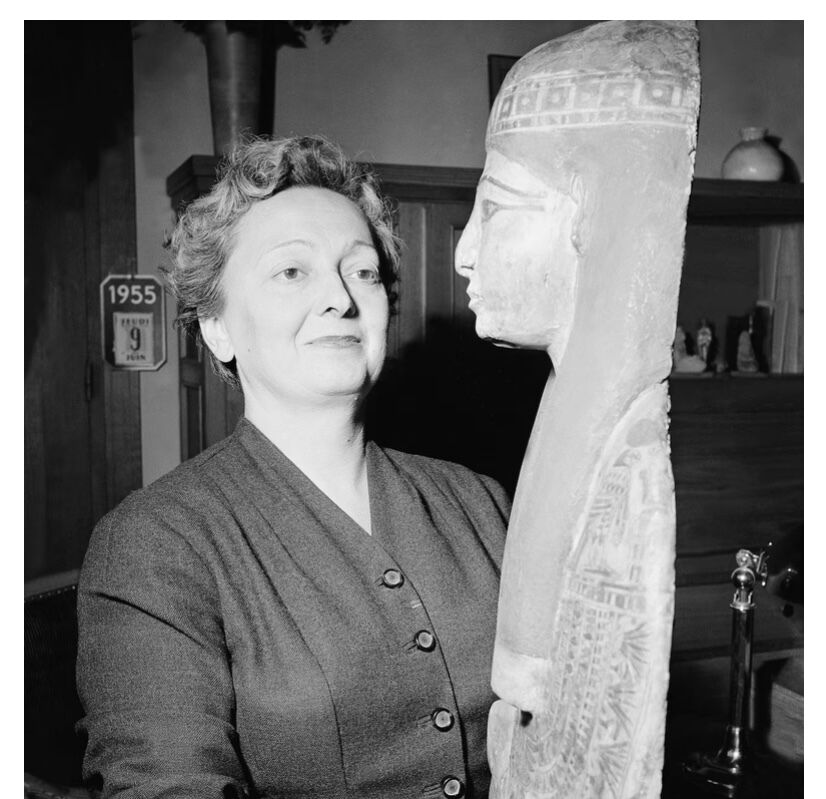

Desroches-Noblecourt, acting chief curator of Egyptian antiquities at the Louvre Museum in Paris and an adviser to the Egyptians, spoke out against this. She urged Egyptian officials not to accept this catastrophic loss of their cultural heritage.

"It was like preaching in the desert," she recalled. "They kept telling me, 'You're wasting your time. Why are you doing this? These are not even French monuments." For her, this argument was nonsense: "I was fighting for what was mine as a citizen of the world and for the honor of humanity."

Desroches-Noblecourt advocated for the most difficult archaeological rescue in history-a project of almost unimaginable scale and complexity aimed at moving fragile sandstone temples to higher ground. The enormous engineering challenges were accompanied by a complex process of seeking international cooperation at a time of escalating global political tensions. In an increasingly divided world, Desrosch-Noblecourt's vision was seen as Don Quixotic and hopelessly misguided. But this did not stop her.

A rebel

All her life, Desrosch-Noblecourt rebelled against men who tried to tell her what she could and could not do. In the rough, male-dominated world of archaeology, women were still extremely rare, and as the first prominent female archaeologist in France, she was shunned from her earliest days in the profession.

In 1938, when Desroches-Noblecourt was named the first female scientist at the French Institute of Oriental Archaeology, an elite Cairo-based research center for the study of ancient Egypt, her male colleagues revolted, refusing, as she later said, to accept: "To share the library or even the dining room with me. They said I would fall and die in the field."

A member of the French Resistance during World War II, she faced several Nazi interrogators after her arrest in December 1940 on suspicion of espionage. She refused to answer the Germans' questions and rebuked them for their lack of education. Exhausted by her defiance and their inability to provide solid evidence against her, they finally let her go.

At the end of her life, she told the interviewer: "You know, you can't achieve anything without a fight. I was never looking for a fight. I became a fighter out of necessity."

Derosh-Noblekour's struggle to save the churches began in the late 1950s after Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser announced the Aswan Dam project. After months of relentless lobbying, she finally gained the support of UNESCO, the UN cultural agency, and Sarwat Okashi, Egypt's Minister of Culture, who in turn convinced Nasser to approve the rescue plan.

In 1960, the Louvre curator and her allies launched a public relations campaign to inform the world of the threat to the antiquities and raise money to cover the astronomical costs of their rescue. From the very beginning, they faced huge obstacles.

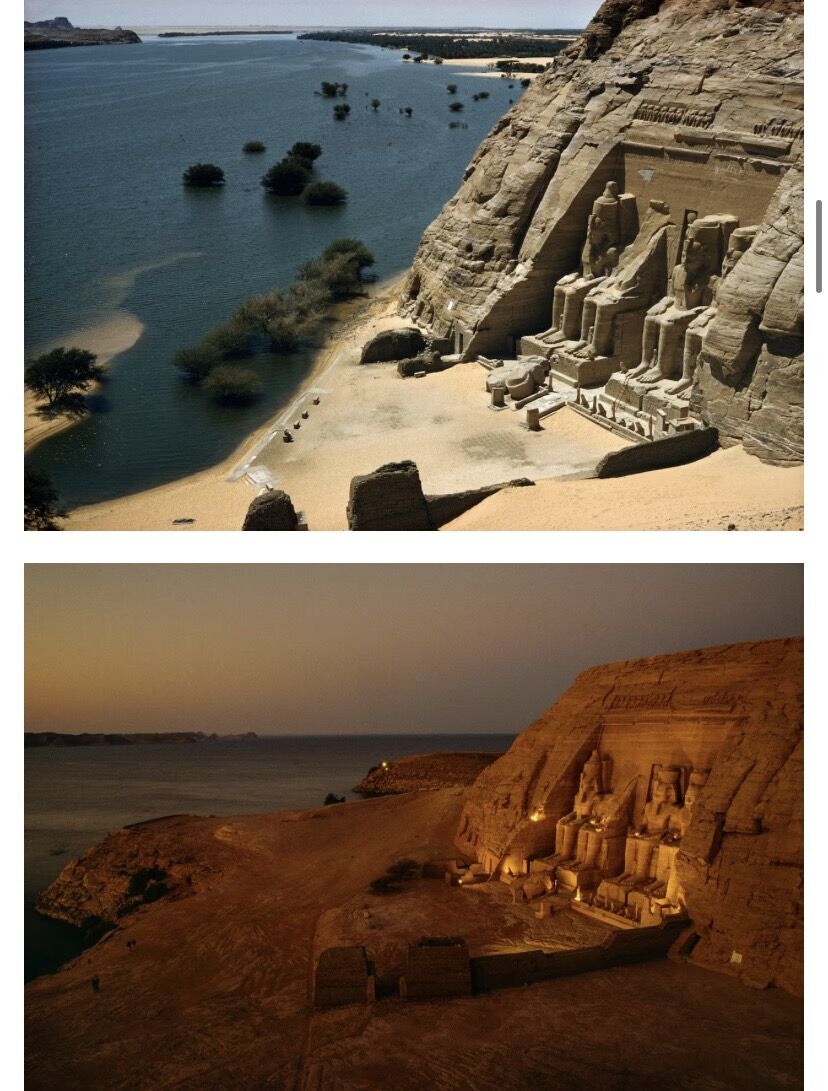

Most engineering experts believed that no matter how much money was invested in the project, the temples could not be moved without irreparable damage. The greatest concern was raised about the majestic twin temples of Abu Simbel, built on a cliff overlooking the Nile by Egypt's greatest pharaoh, Ramses II. Four 66-foot-tall statues of Ramses were carved into the rock, the complex was built around 1250 BC and is considered to be as "fragile and precious as the finest crystal."

The uncertainty of the project was compounded by strong anti-Nasser sentiment in the West, which began with the 1952 military coup that brought him to power and ended British and French de facto control of Egypt. Nasser's staunch refusal to ally with non-Arab countries and his acceptance of Soviet aid was particularly painful for Western governments, including the Eisenhower administration, which not only refused to support the rescue effort but actively tried to prevent it.

Read also: Underwater cemetery found in the US.

Doing the impossible

Without large-scale financial assistance from Western countries, particularly the United States, the project was doomed. Then an incredible savior, Jacqueline Kennedy, appeared on the scene. Only a few months after her husband became president in 1961, the new first lady suggested that he reconsider the US opposition position. Thanks to her influence, President John F. Kennedy immediately appealed to Congress to allocate enough money to provide a rescue. In the end, some 50 countries joined the United States in providing more than $80 million, making the operation the best example of international cultural cooperation the world has ever known.

By the summer of 1968, the race was eventually won. The temples of Abu Simbel cut into large blocks and reassembled like a huge Lego set, were installed in their new location without losing a single stone or seriously damaging it. It was the same with other, smaller temples. The Egyptian president was so grateful that he presented Jacqueline Kennedy and the United States with the Temple of Dendur, which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Ironically, the only two women who played a decisive role in this iconic rescue apparently had no idea that the other was a key player in the fight. Both Desroches-Noblecourt and Kennedy were working behind the scenes. Neither of them sought or received public attention for their achievements, caring not about merit but about getting the job done.

As a reminder, we have already written about the incredible discovery of a sword embedded in a stone.

If you want to get the latest news about the war and events in Ukraine, subscribe to our Telegram channel!